Publishing and analysing data: mySociety's workflow

Originally published on: https://www.mysociety.org/2022/09/13/publishing-and-analysing-data-our-workflow/ (opens new window)

I recently blogged about the data we’re publishing and making use of in mySociety’s climate programme (opens new window) (and how we want to help people make use of it!). This blog post explores behind the scenes how we’re managing that data, using the GitHub ecosystem and Frictionless Data standards to validate and publish data.

# How we’re handling common data analysis and data publishing tasks.

Generally we do all our data analysis in Python and Jupyter notebooks. While we have some analysis using R, we have more Python developers and projects, so this makes it easier for analysis code to be shared and understood between analysis and production projects.

Following the same basic ideas as (and stealing some folder structure from) the cookiecutter data science (opens new window) approach that each small project should live in a separate repository, we have a standard repository template (opens new window) for working with data processing and analysis.

The template defines a folder structure, and standard config files for development in Docker and VS Code. A shared data_common library builds a base Docker image (for faster access to new repos), and common tools and utilities that are shared between projects for dataset management. This includes helpers for managing dataset releases, and for working with our charting theme. The use of Docker means that the development environment and the GitHub Actions environment can be kept in sync – and so processes can easily be shifted to a scheduled task as a GitHub Action.

The advantage of this common library approach is that it is easy to update the set of common tools from each new project, but because each project is pegged to a commit of the common library, new projects get the benefit of advances, while old projects do not need to be updated all the time to keep working.

This process can run end-to-end in GitHub – where the repository is created in GitHub, Codespaces can be used for development, automated testing and building happens with GitHub Actions and the data is published through GitHub Pages. The use of GitHub Actions especially means testing and validation of the data can live on Github’s infrastructure, rather than requiring additional work for each small project on our servers.

# Dataset management

One of the goals of this data management process is to make it easy to take a dataset we’ve built for our purposes, and make it easily accessible for re-use by others.

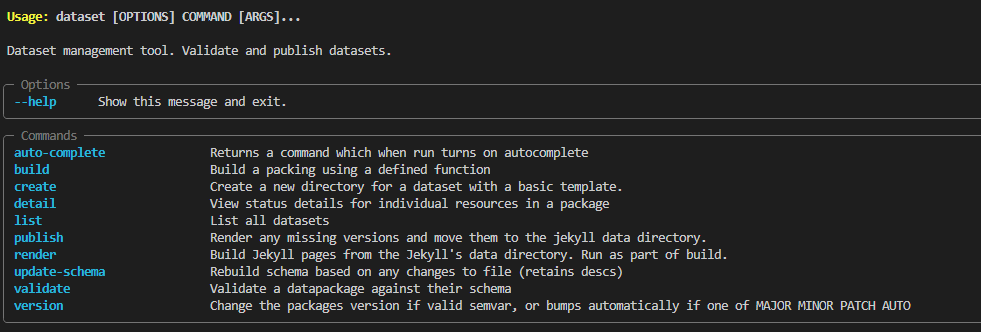

The data_common library contains a dataset command line tool – which automates the creation of various config files, publishing, and validation of our data.

Rather than reinventing the wheel, we use the frictionless data standard (opens new window) as a way of describing the data. A repo will hold one or more data packages (opens new window), which are a collection of data resources (opens new window) (generally a CSV table). The dataset tool detects changes to the data resources, and updates the config files. Changes between config files can then be used for automated version changes.

# Data integrity

Leaning on the frictionless standard for basic validation that the structure is right, we use pytest (opens new window) to run additional tests on the data itself. This means we define a set of rules that the dataset should pass (eg ‘all cells in this column contain a value’), and if it doesn’t, the dataset will not validate and will fail to build.

This is especially important because we have datasets that are fed by automated processes, read external Google Sheets, or accept input from other organisations. The local authority codes dataset (opens new window) has a number of tests (opens new window) to check authorities haven’t been unexpectedly deleted, that the start date and end dates make sense, and that only certain kinds of authorities can be designated as the county council or combined authority overlapping with a different authority. This means that when someone submits a change to the source dataset, we can have a certain amount of faith that the dataset is being improved because the automated testing is checking that nothing is obviously broken.

The automated versioning approach means the defined structure of a resource is also a form of automated testing. Generally following the semver rules for frictionless data (opens new window) (exception that adding a new column after the last column is not a major change), the dataset tool will try and determine if a change from the previous version is a MAJOR (backward compatibility breaking), MINOR (new resource, row or column), or PATCH (correcting errors) change. Generally, we want to avoid major changes, and the automated action will throw an error if this happens. If a major change is required, this can be done manually. The fact that external users of the file can peg their usage to a particular major version means that changes can be made knowing nothing is immediately going to break (even if data may become more stale in the long run).

# Data publishing and accessibility

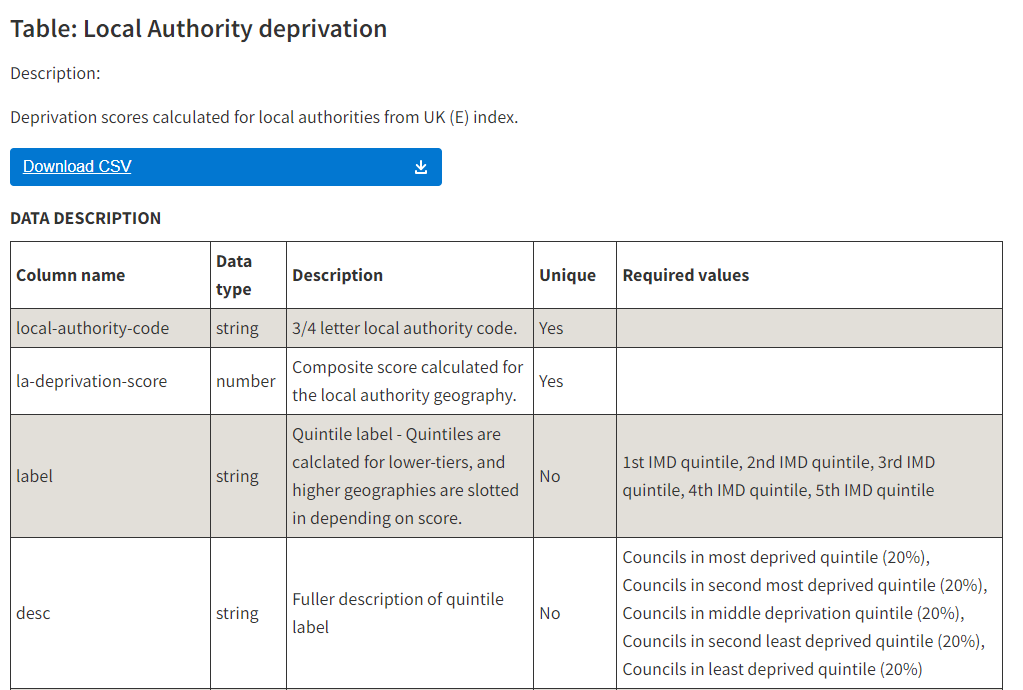

The frictionless standard allows an optional description for each data column. We make this required, so that each column needs to have been given a human readable description for the dataset to validate successfully. Internally, this is useful as enforcing documentation (and making sure you really understand what units a column is in), and means that it is much easier for external users to understand what is going on.

Previously, we were uploading the CSVs to GitHub repositories and leaving it as that – but GitHub isn’t friendly to non-developers, and clicking a CSV file opens it up in the browser rather than downloading it.

To help make data more accessible, we now publish a small GitHub Pages site for each repo, which allows small static sites to be built from the contents of a repository (the EveryPolitician project (opens new window) also used this approach). This means we can have fuller documentation of the data, better analytics on access, sign-posting to surveys, and better sign-posted links to downloading multiple versions of the data.

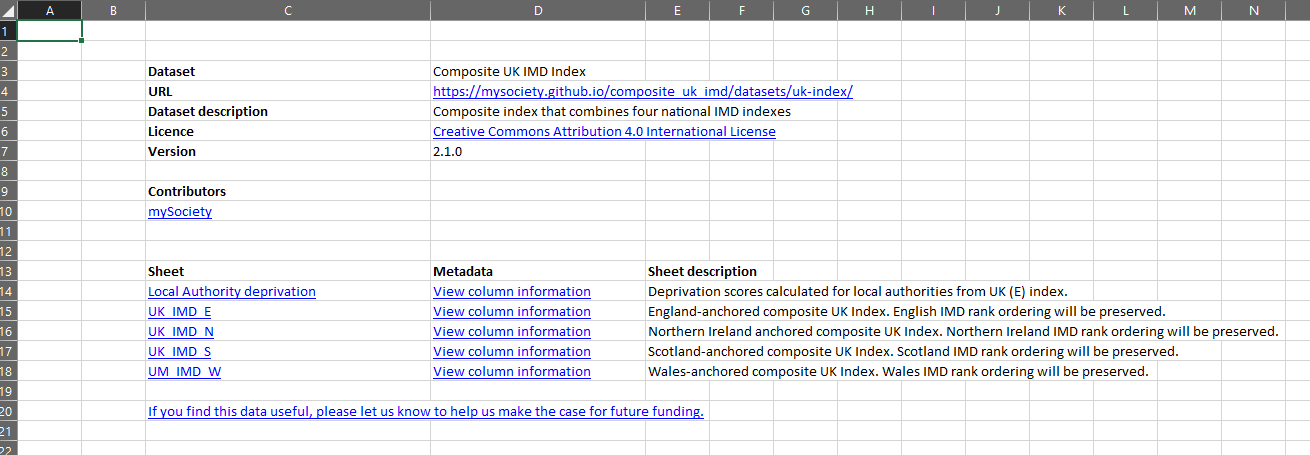

The automated deployment means we can also very easily create Excel files that packages together all resources in a package into the same file, and include the meta-data information about the dataset, as well as information about how they can tell us about how they’re using it.

Publishing in an Excel format acknowledges a practical reality that lots of people work in Excel. CSVs don’t always load nicely in Excel, and since Excel files can contain multiple sheets, we can add a cover page that makes it easier to use and understand our data by packaging all the explanations inside the file. We still produce both CSVs and XLSX files – and can now do so with very little work.

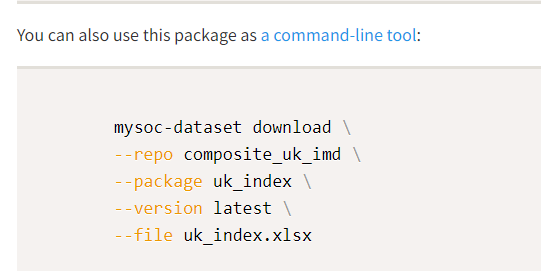

For developers who are interested in making automated use of the data, we also provide a small package (opens new window) that can be used in Python or as a CLI tool to fetch the data, and instructions on the download page on how to use it (opens new window).

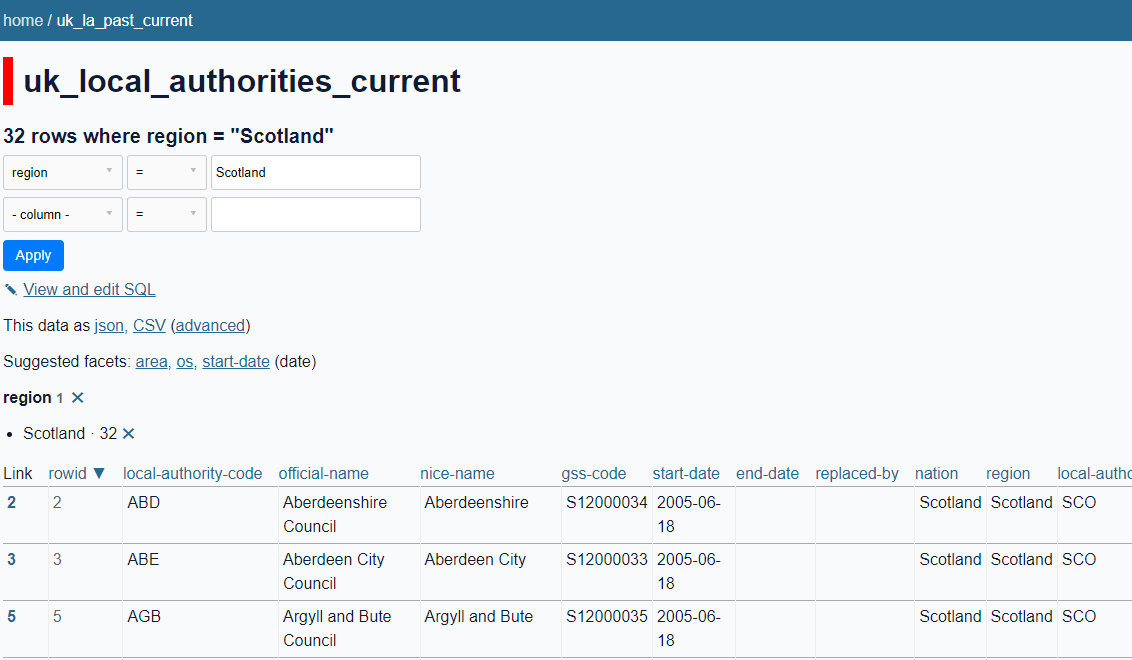

At mySociety Towers, we’re fans of Datasette (opens new window), a tool for exploring datasets. Simon Willison recently released Datasette Lite (opens new window), a version that runs entirely in the browser. That means that just by publishing our data as a SQLite file, we can add a link so that people can explore a dataset without leaving the browser. You can even create shareable links for queries: for example, all current local authorities in Scotland (opens new window), or local authorities in the most deprived quintile (opens new window). This lets us do some very rapid prototyping of what a data service might look like, just by packaging up some of the data using our new approach.

# Data analysis

Something in use in a few of our repos is the ability to automatically deploy analysis of the dataset when it is updated.

Analysis of the dataset can be designed in a Jupyter notebook (including tables and charts) – and this can be re-run and published on the same GitHub Pages deploy as the data itself. For instance, the UK Composite Rural Urban Classification (opens new window) produces this analysis (opens new window). For the moment, this is just replacing previous automatic README creation – but in principle makes it easy for us to create simple, self-updating public charts and analysis of whatever we like.

Bringing it all back together and keeping people to up to date with changes

The one downside of all these datasets living in different repositories is making them easy to discover. To help out with this, we add all data packages to our data.mysociety.org (opens new window) catalogue (itself a Jekyll site that updates via GitHub Actions) and have started a lightweight data announcement email list (opens new window). If you have got this far, and want to see more of our data in future – sign up (opens new window)!